Meet a Medievalist Maker: Sara Charles

The cover of The Medieval Scriptorium: Making Books in the Middle Ages by Sara Charles

“Meet a Medievalist Maker” is an ongoing series of blog posts introducing our members and the work they are doing. Each post is organized around our Four P’s: a project they are working on (or have completed but want to highlight); their process: medium, etc; a peek at their work: images or excerpt; and a prompt: instructions for a brief exercise they share to allow readers to experience/explore their process. Would you like to write a post introducing yourself and your work? Send us an email!

My name is Sara Charles and I am a medieval manuscript enthusiast. I trained as a librarian and through that became more interested in manuscripts – particularly in the way they were made. I like to explore all aspects of manuscript making, from the preparing of parchment, to making inks and pigments, to the final step of bookbinding. This means getting right down into the dirty, smelly business of working with natural products and using my hands. It is not very glamourous, but it allows me to experience the sights, smells, sounds and textures of manuscript processes. I enjoy sharing my findings with a wider audience, through talks, workshops and social media.

Project

I’m in that strange eerie calm between projects – I’m still recuperating from finishing my PhD and not quite ready to commit to a new project and relinquish my spare time again (although ideas are bubbling away!). So, this summer has given me an excellent opportunity to revisit my (many) unfinished projects – one of being a stack of yarn that I dyed a couple of years ago using medieval dyes: lac (pink), madder (orange), weld (yellow), woad (blue) and alkanet (purple). I knitted the yarn into squares using a basic knit stitch with the intention of sewing them together into a blanket – but then I put them in a cupboard and got distracted by other things. This summer, while feeling a bit unmoored from not having any deadlines, I dug out the squares, brushed off the cat hair and arranged them by colour and gradient. Numbering the squares (because it’s not beyond the realms of possibility that they will go back into the cupboard again for another few years), I stacked them into piles and am now slowly sewing them together. It’s not skilled sewing (neither is the knitting) but it is a joy to work with my hands using yarn that I dyed, knowing that I’m using the same vibrant natural colours that medieval people would have worn.

Dyed wool hanging up to dry: blue (woad), forest green (weld overdyed with woad) and yellow (weld)

Knitted squares labelled and ready to sew together

Another minor sideline is experimenting with the method of incising gold leaf with patterns, as became fashionable in thirteenth century manuscripts. As usual, it starts with me thinking ‘well, let’s just have a go, see if I can figure it out’. And as usual, it turns out to be a lot more skilful and complex than anticipated. So far, I’ve wasted a lot of gold. It seems to me the trick is working out the sweet spot between when the gesso is too wet and when it is too dry – too wet and applying the gold turns it to sludge, too dry and it’s hard to impress into the surface. But it is fun to tinker with these things when you have the time.

Example of incised gold background from the Huth Psalter (BL, Add MS 38116, fol. 8v)

Process

This is something that I struggle to describe in academic terms. My flippant take on it would be I just have a go and see what happens – but of course it is informed by various factors: studying surviving examples, researching classical and medieval recipes, and adapting to the modern resources available. Various terms for these practices have been suggested: historical remaking, medieval practitioning, experimental history. Take your pick – I don’t have a preference. The best way I can describe what I do is anecdotally. When I was doing my MRes in the History of the Book, we had a visit to a working printers. While we were watching one of the bookbinders deftly hammering the spine into a rounded shape, I became acutely conscious of us, the ‘academics’ looking over his shoulder and nodding sagely to each other – ‘yes, that’s how they describe it in the textbooks’. And there seemed to be such a chasm between the skilled labourers in the workshop doing the bookmaking and we, the academics, peering over their shoulders – and I knew that I wanted to be the person bridging that gap – understanding the process through physical immersion, using my hands to create something tangible, while being able to tie that to the historical record and to articulate that knowledge. (I will caveat that story by saying I absolutely still cannot hammer a rounded spine, but at least I’ve tried and know how hard it is.)

Another term that I have recently learned is ‘critical fabrication/fabrication’ - when you use what and who you know from the historical record to weave a narrative (but stopping short of historical fiction). I employed this technique in my book The Medieval Scriptorium, where each chapter starts with a vignette from the point of view of a medieval manuscript maker, such as a scribe or a parchment maker. These were my favourite parts of writing the part, so I am absolutely delighted to know that there is an accepted academic term for this!

Peek

My book The Medieval Scriptorium has just come out in paperback. It is a journey through the medieval manuscript making process in the Latin Christian world, often drawing on my own experiences in manuscript making. I was overwhelmed by the positive reception it got last year, and it has led to many invitations to give talks and be on podcasts. Being given the opportunity to share my enthusiasm for medieval manuscripts and the people that created them is an absolute delight.

I also have my website: www.teachingmanuscripts.com, where I share my experiences of manuscript processes and medieval pigments.

My break from writing has given me a chance to get back to creating medieval miniatures again. I am always drawn the bestiaries, particularly the Aberdeen Bestiary, with their weird and wonderful animals. The unashamed use of gold and bold pigments are such fun to recreate. I try to use the pigments most appropriate to the time period, so there is plenty of lapis lazuli and red lead.

Prompt

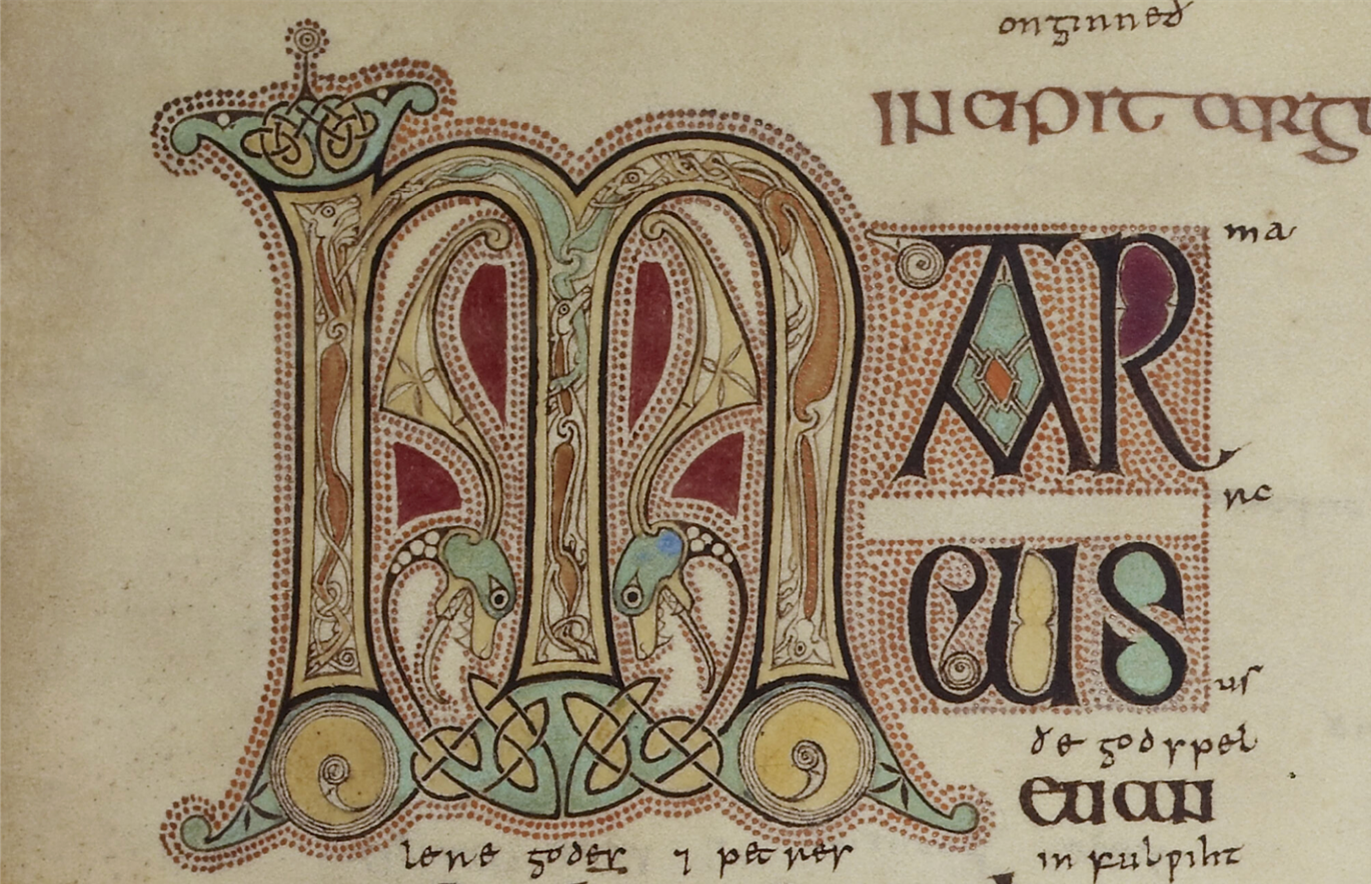

There are quite a few simple procedures that you can do at home to experience manuscript making. One easy one is to select an image from a digitised manuscript, for example, the Lindisfarne Gospels, print it off and simply trace the image. It gives you a real idea of just how intricate and complex those early English designs are when you try to follow the lines with a pencil. And then in your mind’s eye situate yourself in the northeast of England in the eighth century, using a stick of lead to draw out these designs and then painting them with a hairs-breadth paintbrush to create those fine lines. It gives a real insight into just how skilled those artists were!

BL, Cotton MS Nero D IV, fol. 90r

Another simple process is to create verdigris pigment by suspending copper strips over white vinegar in a sealed jar. A green patina will build up on the copper, which you can scrape off and grind up with gum arabic. It’s interesting to watch the colour build up on the copper everyday and it’s a good idea to take regular photos to document the progress. Watch those vinegar fumes though – it’s a good idea to wear a mask when scraping off the pigment.

Copper strips suspended over vinegar

The thing I always stress is that the end result is not necessarily the goal – the immersion in the process is the most rewarding thing. It’s experiencing the sights, sounds, smells and textures as you go along, its understanding how your body is involved in the process, its connecting with the past through a tangible set of steps. It doesn’t matter if you don’t end up with the result you expected (believe me, it happens quite often!) – what is important is how you were present in the process, how your mind and body engaged with the steps and worked things out – exactly as they would have done in the medieval period.