Meet a Medievalist Maker: Becca Drake

“Meet a Medievalist Maker” is an ongoing series of blog posts introducing our members and the work they are doing. Each post is organized around our Four P’s: a project they are working on (or have completed but want to highlight); their process: medium, etc; a peek at their work: images or excerpt; and a prompt: instructions for a brief exercise they share to allow readers to experience/explore their process. Would you like to write a post introducing yourself and your work? Send us an email!

I am writing this in a room full of paper cuttings: bits of old poems, new poems, and would-be-poems fragmenting the table and floor. My name is Becca Drake, and I am a researcher, poet and printer based in York. As a creative, I balance a lot of things. One is teaching English literature at the University of York. Another is working on research-led community engagement projects, all broadly captured under the umbrella ‘Water Poetics’. Related to this, I have an article coming out soon about some of my creative critical research with the Hull Maritime Museum, in Digital Scholarship in the Humanities. I also founded a micro poetry letterpress, Little Hirundine, as a way of engaging with poetry on a slower, more tactile timescale. Another thing I am balancing is my poetry. My first poetry book Unstill Landscapes (Guillemot, 2025) is a bit of an extended experiment in form recording my personal, often autobiographical and embodied responses to landscape. It is also a bit of writing with medieval texts as an outlet for many of the ideas in my doctoral research, which was all about the medieval sea in English and Icelandic romance, and how people lived with it as an agent from day to day. I find that all these areas of my work tangle up and need each other to grow.

Process:

I first started writing poetry as a way of processing medieval texts – writing into them poetically gave me an alternative way of knowing that I needed to better understand them. For my PhD, I was studying heroic poems such as Havelok the Dane, and sagas such as Ketils saga hængs, trying to piece together historical environmental fragments left behind in these texts. I found writing my own poetry a helpful practice for filling in the gaps, or constructing imaginary medieval landscapes. For example, I wrote Awntyrs to help myself understand how the fenland landscape in Havelok and the local onshore fishing industries of late-medieval Grimsby might have shaped the narrative of the romance. To write this poem, I crumbed together my research into North Sea fish species, North Atlantic trade, and late-medieval environmental crisis around the medieval North Sea basin with my embodied experience of walking in the fens south of Grimsby.

In terms of responding to medieval texts through poetry, I think I am gathering fragments – of text, place, personal experience – and reassembling them on the page. Sometimes using scissors or creating photocopy palimpsests, and sometimes letting misremembered bits from what I have read or encountered silt up in my mind. Those half-remembered, or misheard bits seem important; it’s not about a crisp or even historically accurate representation of past narratives or landscapes, but a kind of feeling it out in the present. I think this is one of the advantages of creative approaches to medieval literary criticism, in that it allows a different kind of knowing that might lose some specificity but perhaps gains something new from a kind of poetic vagueness.

Some contemporary poetry books I return to that experiment with versioning texts in a very playful way are All Keyboards Are Legitimate (Guillemot, 2023), edited by Suzannah V. Evans, and Meddle English (Nightboat Books, 2011), by Caroline Bergvall. I am interested in how the poetry collected in these books allows a generous elasticity between an original text and its version/revoicing. On revoicing, the Revoicing Medieval Texts network, organised by Francesca Brooks, Carl Kears, and Fran Allfrey, has been a really great space for me for exploring creative ways of working with medieval texts – I was fortunate to attend some of their events just as I was gathering confidence with my own poetry.

Project:

Some of the poems in Unstill Landscapes aren’t obviously medieval, especially to a non-medievalist audience, but there are lots of easter eggs and medieval influences if you know where to look. ‘The Surfer’ (below) began life as a creative translation of a sequence of verses in Ketils saga hængs, where the troll-woman Forað describes travelling down the coast from Norway to Sweden. An early draft of the poem shows a bit of my process for some of the poems in the book – which is taking medieval texts and pulling at some of their threads, loosely translating, versioning, or associating meanings. When I wrote this early draft, I had been processing my translation of Ketils saga, thinking about the language of landscape landmarks in the saga text and trying to decide which words and meanings to settle on.

By the final revision of this poem in Unstill Landscapes, I have reabsorbed the medieval character into the lyric ‘I’ of the poem, but a few clues to the medieval remain: ‘ness’, the Old Norse-Icelandic word for headland, ‘haggard… headland’, which plays with alliterative metre for just a couple of lines, and the image of the ‘ninth wave’ – in Old Norse mythology, the sea god Rán has nine daughters, who are often represented as waves (with prominent noses).

Peek:

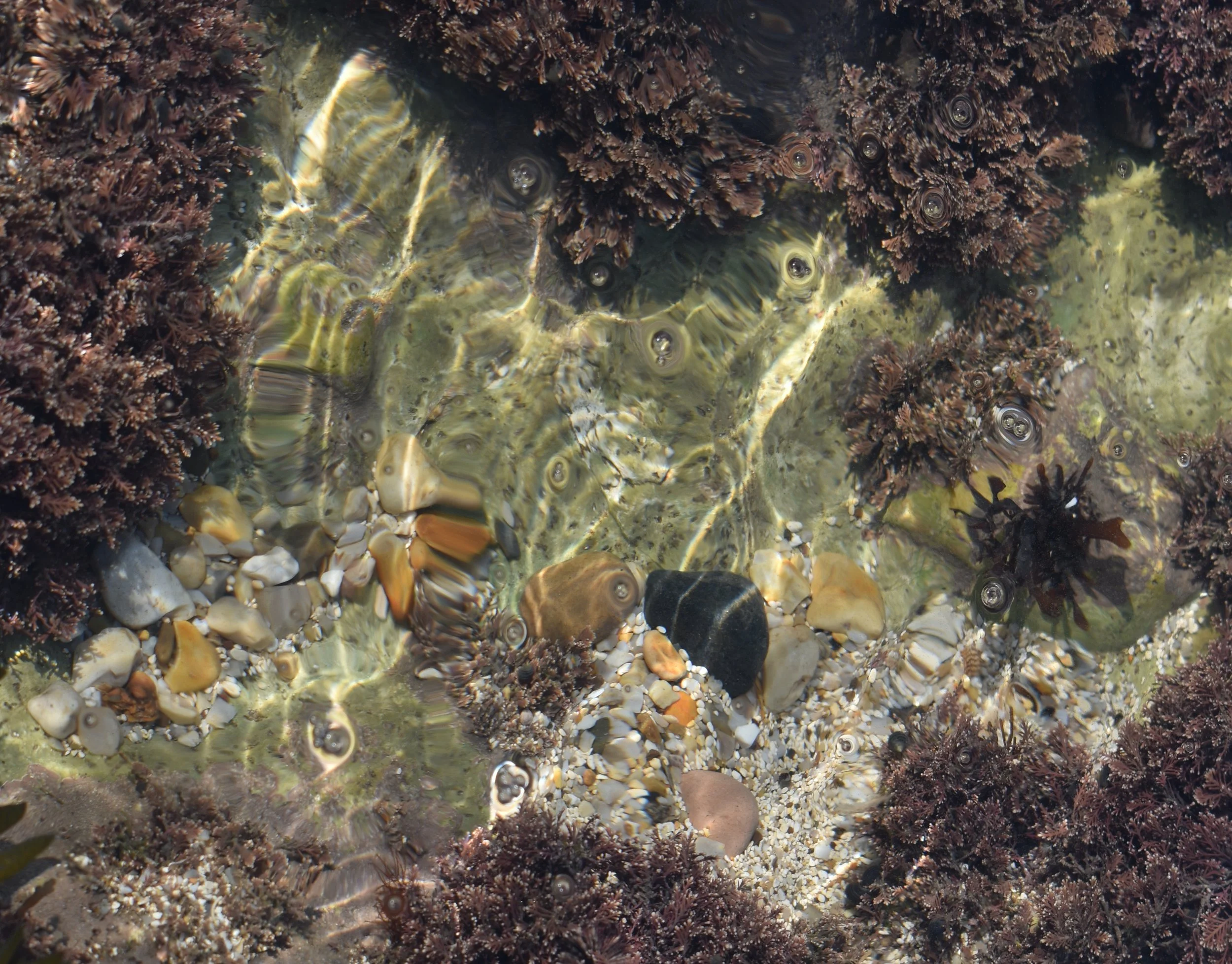

At the moment, I am interested in versioning medieval texts by borrowing form rather than meaning. I am currently working with alliterative half lines to poke at themes of belonging and isolation around the landscapes of the Yorkshire East Coast. When you go to places like Thornwick Bay and look at the rock formations, or you think about wave patterns, they look like an alliterative text or a passage of elaboratio – if these landscapes asked for any poetic form, it would be interlocking and compounded; which is quite a medieval aesthetic.

Prompt: Writing with a Saga:

Choose a saga. An accessible one is Egils saga. It's about a poet and so there are some great prosimetric (part prose, part poetry) passages to play with. A cheaply available translation is the Bernard Scudder translation for Penguin Classics (2005). Photocopy one page of the saga. Cut out all the repeated phrases, idiomatic language, or saga cliches. With the text that remains, lay out the prose in a single long line (use scissors to help you do this), and reform the text as poetic free verse.

Suggested Reading:

Becca Drake, Unstill Landscapes (Guillemot, 2025)

Caroline Bergvall, Meddle English (Nighboat Books, 2011)

Suzannah V. Evans, ed., All Keyboards are Legitimate: Versions of Jules LaForge (Guillemot, 2023)

Thanks for a super post, Becca, and a wonderful introduction to your creative practice! You can find Becca on her website (www.beccadrake.weebly.com) and on Instagram (@r.l.drake).